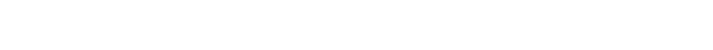

The Ethos of Writing, Alexander Parsons Talks to Junot Díaz

La idiosincrasia de la escritura

Junot Díaz

The Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series is presented a Junot Diaz reading a propos of his new story collection This Is How You Lose Her, one of the most anticipated books of the year. At the heart of the stories is Yunior, an irresistible and reckless young man from his earlier story collection Drown. The new book focuses on the power of love–obsessive love, illicit love, maternal love. Here is a conversation between the author and Alexander Parsons.

* * *

Alexander Parsons: You really show a mastery of dispersive style. You’ve used the first person point of view in your work, but in your latest collection, you chose the second person. Could you talk to us about the appeal of that voice?

Junot Díaz: I think what happens with the second person is that most of us know that in practice, it is a difficult mode because of how it’s simultaneously intimate and distant. If you spent your childhood like I did, you’re constantly under the influence of that second person command: “You, you, you!” So it’s a form in which you have to overcome many people’s resistance. The thing with me, and with most artists, is that when you discover that you have a weakness in a mode, you try to pour yourself into it. I can write in the first and third voices far more contritely. I always knew it was a deep weakness when I encountered those old war stories, where I felt I knew the person. I had been trying to write those kinds of stories on my own, and I knew it was a problem. So in each of my books, I always try to have something in second person, if only to exercise it. In a book, you never know when you’re going to need a mode. And so if you keep an area weak, you’re going to have to learn it on the fly rather than practice your weaknesses and be ready to go.

AP: With that perspective in mind, in your latest collection, you use the female voice a lot more, and you are writing fuller and stronger female characters. Do you feel that was a weakness that you really wanted to grasp, or just something you wanted to explore? Where do you stand in relation to women in your works?

JD: First of all, as an artist, and especially if you are an artist of color, there is this amazing impulse to rely on your work, so that no one has to talk about your artistry. The best way that people can obviate the hard work that goes into being a writer is to just sidestep your formal interest or formal experimentation to do the kind of stuff that makes a story possible to structure. The best way for folks not to have to recognize or tangle with it is to do something you might call “biographying,” where they don’t write characters, they just are their characters, and that’s a great way to be really lame. It’s exceptionally redundant, but it also ducks the questions that an artist like me is trying to raise about what sort of masculinities will we feel more comfortable reading about, and how that has nothing to do with the masculinities we encounter. So, you encounter an average male asshole on the street but you don’t want to actually be that. Or as my sister says, none of my girlfriends have trouble fucking these dudes; they just don’t want to be the guy. So for me, when I think about another huge weakness as a male writer, it’s true… You don’t have to have washed up from the same island as Wonder Woman for you not to be an intrinsically bad writer of women. As men, we spend our first forty years living in a culture that reinforces the masculine privilege of not seeing women as fully human… And as an artist who grows up seeing women as not fully human, you reproduce that. The average man starts writing women at level zero, and if he practices his whole life, he gets to twelve out of a hundred. He starts writing about men at level seventy-five! Because, whether you accept it or not, we live in a society that tells women that they are not human, and men are. I grew up with four sisters, and they more readily acknowledged my humanity than I theirs, and so I think these are factors that don’t apply to everyone. But a writer who ignores them misses the opportunity to make a necessary intervention with their art. I work with my male student writers, and they are universally abysmal. But we don’t generally say in class, “gather round, gentlemen, you fucking suck.” For the most part, I think male writers should hang a vag around their necks and say, “I suffer now.”

AP: So in terms of taking risks, you have a wonderful voice that jumps off the page, it’s polyglot, it’s filled with all sorts of slang, and you just roll along. I wonder, when you began writing, is that the voice that you heard, one that announced itself more or less fully formed? Or is it something that you really fought to develop?

JD: I’m interested in this, because especially when it comes to the question of elaborating “a voice” as an artist, some might call it an ethos. Before anything, as a writer you have to determine what your ethos of writing is, but even before that, what your ethos of reading is. Most young writers can’t articulate what their ideas are about the act of reading, and I thought about that before I began to think about elaborating a voice that could bring together all the disparate parts of me. . In the beginning, my work was so bad. And one of the things that was helpful was not approaching it from a writer’s perspective, which is a dead end. A far more generous and productive approach is to ask yourself what your ideas about reading are. The average reader is a million times more open and generous than the average person in a writing workshop. Most of my students are writing for other writers, with whom they are locked in a sort of deathly competition. So there’s an enormous amount of fear in them that suggests they might be doing something wrong, and none of that comes from readers. Readers will put up with a bunch of nonsense, and they are always happy to see the books they love. You’re not going to dislodge a reader’s love for a book, and readers bring a lot to the books. They excuse all our writerly flaws, they make up for the gaps we have in our calendars. If our plots don’t work well, readers stitch them together to make them work… Readers are happy to see you. So when I realized that I was really writing for readers, I was good to readers. As long as I gave them the classic pleasures of character and storytelling, they would put up with a lot of things. Readers of the Lord of the Rings put up with thousands of images of Elven poetry because they love the books, and they don’t understand any of that shit! The baseline for coming up with a voice for readers is trying to harmonize with the generosity of the form we’re in. If only more writers turned their eye away from other writers, toward readers, these beautiful generous people and who are way smarter than most of us writers give them any credit for. When I hear my students say, “Oh, that’s too much of a foreign language!” I say, “What reader are you talking about?” Before we can even get to a voice, I always tell them, “Let’s get to the ethos of reading, so at least you know where you’re at.” When you have a generous environment, you’re far more likely to experiment with your voice, and you’re far more likely to be tolerant of your errors.

AP: Why hasn’t Junot Diaz written any science fiction and fantasy? Is it that you feel that even though it’s part of your ethos of reading, the formal constraints of it are not what interest you in terms of format, or can we expect you to come out with your own trilogy?

JD: I do love all the nerd forms. If there’s a competition for nerds here, I might not make it to the top ten, or even make the Olympic team, but I’ll give you a good run for it. Part of it is my own set of limitations as a writer. I’ve tried to write these things, but am exceptionally bad at these genre forms. Even my most tolerant reader friends will say, “Dude, don’t show this to anyone!” Part of it is that I’m slow. I’m trying to write this weird apocalyptic monster novel. I keep having dreams. I don’t know anyone else who grew up in a house with those huge, scary, Catholic paintings… They had one at my house of St. Michael smashing a dark-skinned devil with one of those curved angel swords. When I was a kid, they looked forty feet tall, and so I always had the idea that I would write a story about forty-foot monsters who were kind of angelic, but no one liked it.

AP: Well, getting back to the short story collection, I was thinking about them in relation to Oscar Wao. And Oscar has a very open heart; he’s doomed by it to a degree. Do you think that Yunior suffers from that? He seems to inhabit this area of loss rather than love; he seems to always be in mourning. So could you talk a little bit about Yunior and his situation, and whether he seems fated to mourn the loss of his relationships… or do you see yourself working with him further down the line?

JD: I think I always thought of these stories kind of simplistically; I believe they open an opportunity for people to encounter themselves. Not so much that you walk away from art in some ways healed, or made better, but art has this ability to take those who spend their time in this society rarely thinking about our human, flawed, imperfect yet utterly beautiful self. Art gives us a chance to be in that human presence, and that’s often really hard. If anyone grew up like me, spending most of my time pretending I was better than I am, as if we were not supposed to have flaws or make mistakes, we’re not supposed to be conflicted, we’re supposed to be these smoothly functioning machines. And art gives us a chance to, for a moment, drop our act. So that’s what I think this work gives us an opportunity to do, and as far as Yunior is concerned, I guess that he’s a character that, like many of us, has had a remarkably difficult childhood. He doesn’t make anything of it, which always fascinated me. As a character he never scores that he has a father who despises him, he misses his native country, his immigration wasn’t cute, his mother is indifferent, she’s way more interested in his brother, his brother is a borderline sociopath who doesn’t care if he takes his brother’s eye out to make a point… It’s not the best childhood. He really doesn’t make any hay of it, as a narrator he doesn’t describe how he’s suffering, and I think Yunior’s problem with relationships come in this context. He is someone who is so guarded, that had to close himself off to survive, and yet he is desperately longing for love. And I think the idea that our past haunts us in some ways, that our past makes arguments against us that we have to, with our lives, counter, is something that I think about with Yunior. His past is weighing, and he certainly has to figure out a way to tell a certain story. He’s stuck in this weird story in which he tries to figure out a certain story, and I think most of us are in that place.

AP: You said earlier that society is often indifferent to the arts. How did you come to writing, what sustained you? Perhaps tell us of a crucial moment in which you thought, “It’s going to happen,” or “it’s not going to happen.”

JD: I think it’s one of those stories that a lot of us have as narratives; I came from an eminently practical immigrant family. I come from a military family; my father was in the Dominican military, my little brother is a Marine combat veteran who just came back from Iraq, my sister has married into the military… The idea that one of us would become an artist was so absurd because we were so poor, we were on food stamps, the whole nine yards. It was a massively impractical move, but part of what moves this stuff… My writing comes out of my love of reading. Writing would be impossible for me if I didn’t love reading so much. I am a very slow writer. I find writing extremely difficult; I’ve never been a writer who is fluent. I have never said, “Oh, that was a good day of writing,” but many of my friends do. What happens with someone like me is that you’re faced with a family’s granite resistance, adamantium resistance when you’re faced with how difficult the work is. I think the only thing that makes this possible for me is that I love books so damn much. When I was a kid, I constantly dreamed of books that were never written, like the Lord of the Rings having a fifth book, and I would always find it in the library, but before I could check it out I would wake up, and this was a nightly thing. Part of what was happening, of course, is this enthusiasm for reading, and I think it helped push me. If you love something enough, it will help with the discouragement. And I was also, as an immigrant kid, super practical. I was never one of those artists who asked to be supported for months while I wrote. So I always worked delivering pool tables, I worked at a steel mill, and all these other crappy jobs because in my mind was always the thought that you give unto Caesar what you owe him. So I got jobs and then wrote at night, and I thought that was going to be my life. I thought I was going to have a regular mosaic job. Part of why I felt I could do this was the notion that I loved these books so much, that the dreams of these books would keep me together. And I do remember the day when I woke up in my college dorm and realized that it was going to be very difficult for me to become a lawyer or go to school.

AP: What are your thoughts about the work being banned in Tucson, Arizona?

JD: Beyond my own personal statement on what it means to have your work banned, I think the larger question you’re raising is that we’re in such a perverse historical moment in this country. We cannot separate the banning of Latino-themed cultural books in Arizona from the ongoing full-scale attack on ethnic studies programs across the country. Nor can we disentangle the fact that ethnic studies programs most consistently provide young people with a critical lens through which we attempt to view and improve our democracy. Take an ethnic studies class, and you’ll be a way better member of our civic society than otherwise. But, as you well know, the reason that you’re a better member is because you suddenly have a racial, cultural, gender, class lens with which to approach the world, and that is deeply disturbing to these assholes that want to ban this stuff. On top of that, you can’t uncouple any of that from the perverse and inhuman wave of anti-Latino activity that has gripped this country. It is madness! The way we have victimized the Latino community, the way we continually demonize it; it’s like a free for all. If anyone had told me that the real domestic victims of 9/11 were the Latino community, I would’ve been surprised but believed it. I guess it all comes together most explicitly in a place like Arizona, but as a nation, what we’ve mostly shown to our “largest minority group,” and the group whose undocumented labor we are all addicted to, is nothing but cowardice, scorn and cruelty. I think we will one day get the president that we deserve. We don’t have him right now, but we will get a leadership who doesn’t think it’s a good idea to afflict the most vulnerable people in our community, and I think nothing speaks about the decline of national character than a nation which practices the affliction of the weak.

*PHOTO BY CAROLYN COLE

Traducción al español de Eugenia Noriega

La serie Inprint Margarett Root Brown auspició una lectura de los cuentos de Junot Diaz con motivo de la publicación de su nuevo libro This Is How You Lose Her, uno de los títulos más esperados del 2012. En el centro de estas historias se encuentra Yunior, el irresistible e imprudente joven que también aparece en un volumen originalmente titulado Drown. La nueva publicación se enfoca en el poder del amor obsesivo e ilícito igual que en el amor maternal. A continuación presentamos una conversación exclusiva para Literal.

* * *

Alexander Parsons: Muestras una verdadera maestría en el dispersive style. Has escrito desde el punto de vista de la primera persona pero en la reciente colección te decidiste por la segunda. ¿Podrías hablarnos sobre el atractivo de ese recurso?

Junot Díaz: Creo que lo que pasa con la segunda persona es que la mayoría de nosotros sabemos que, en la práctica, es un modo difícil por la manera en que es íntima y distante a la vez. Si tuviste una infancia como la mía, estás constantemente bajo la influencia de la orden que se da en segunda persona: “¡Tú, tú, tú!” Así que es una forma en la que hay que vencer la resistencia de muchas personas. Lo que me pasa a mí, y a la mayoría de los artistas, es que cuando descubres que tienes una desventaja respecto de una forma, tratas de volcarte por ahí. Puedo escribir en primera y tercera persona con mucho más abatimiento. Siempre supe que era una profunda debilidad cuando me encontraba esas viejas historias de guerra que me hacían sentir que conocía a la persona. Estuve intentando escribir ese tipo de historias propias, y supe que era un problema. En cada uno de mis libros trato de hacer algo en segunda persona, aunque sea como ejercicio. En un libro nunca sabes cuándo vas a necesitar una forma. Si dejas que un área de tu escritura siga siendo débil, vas a tener que aprenderla al vuelo, en lugar de practicar tus áreas débiles y estar preparado.

AP: Con esa perspectiva en mente, en tu última colección utilizas mucho más la voz femenina, y estás escribiendo desde personajes femeninos más completos y fuertes. ¿Crees que eso responde a una debilidad que querías dominar, o fue sólo algo que deseabas explorar? ¿Cuál es tu postura respecto de las mujeres en tu obra?

JD: En primer lugar, como artista, y en especial si eres un artista de color, hay un impulso extraordinario de confiar en tu trabajo para que nadie tenga que hablar de tu habilidad artística. La mejor manera en que la gente puede obviar el trabajo duro que implica ser escritor es simplemente soslayar tu interés formal o experimentación formal para hacer el tipo de cosas que hacen que sea posible estructurar una historia. La mejor forma de no tener que reconocer o enmarañarse con eso es hacer algo que podría llamarse “biografiar”, donde uno no crea personajes: simplemente, es sus personajes. Y esa es una excelente manera de ser pésimo. Resulta excepcionalmente redundante; además, elude las cuestiones que un artista como yo trata de plantear acerca del tipo de masculinidades sobre las cuales nos resulta cómodo leer, y cómo eso no tiene nada que ver con las masculinidades con las que de hecho nos topamos. Uno se encuentra en la calle con el macho imbécil promedio, pero de hecho no quiere ser eso. O, como dice mi hermana: mis amigas no tienen ningún problema para acostarse con estos tipos, pero simplemente no quieren ser de ese tipo. Así que para mí, cuando pienso en otra enorme debilidad como escritor masculino, es cierto… No tienes que venir de la isla de la Mujer Maravilla para no ser un escritor de mujeres intrínsecamente malo. Como hombres, nos pasamos nuestros primeros 40 años viviendo en una cultura que refuerza el privilegio masculino de no ver a la mujer como enteramente humana… Y como artista que creció viendo a las mujeres como no del todo humanas, reproduces eso. El hombre promedio empieza a escribir sobre mujeres en el nivel cero, y si practica toda su vida llega a un doce de cien. ¡Empieza a escribir sobre hombres en el nivel setenta y cinco! Porque, ya sea que lo aceptemos o no, vivimos en una sociedad que les dice a las mujeres que no son humanas, y los hombres sí. Yo crecí con cuatro hermanas, y ellas reconocieron mi humanidad con más facilidad que yo la suya. Por eso creo que estos factores no son aplicables para cualquiera, pero un escritor que los ignora se pierde la oportunidad de hacer una intervención necesaria con su escritura. Trabajo con alumnos escritores y todos son universalmente abismales. En clase, no solemos decir: “caballeros, todos ustedes son un asco”. En general, creo que los escritores masculinos deberían colgarse una bolsa del cuello y decir “ahora sí padezco”.

AP: Así que, en términos de tomar riesgos, tienes una estupenda voz que sobrepasa la página. Es políglota y está colmada de todo tipo de argot. Tú sólo sigues la corriente. Pero me pregunto si cuando empezaste a escribir esa voz ¿se anunció a sí misma ya más o menos formada o fue algo con lo que batallaste?

JD: En especial y como narrador, me interesa el momento en que se trata de crear “una voz”. Algunos podrían llamarlo idiosincrasia. Como escritor debes determinar cuál es la idiosincrasia de tu escritura pero, antes que eso, debes saber también cuál es tu idiosincrasia de lectura. La mayoría de los escritores jóvenes aún no logran articular sus ideas en torno al acto de leer –yo mismo cuando empecé a ensayar una voz para unir todas mis partes dispares. Al principio, mi trabajo era muy malo. Una de las cosas que me ayudó fue no acercarme a esos ensayos desde la perspectiva de un escritor, que es un callejón sin salida. Un enfoque mucho más generoso y productivo es preguntarte cuáles son tus ideas sobre la lectura. Un lector promedio es un millón de veces más abierto y generoso que la persona promedio en un taller de escritura. La mayoría de mis alumnos escriben para otros escritores, con quienes tienen algo así como una competencia mortal. Están llenos de un miedo enorme que sugiere que tal vez están haciendo algo mal. Y nada de eso viene de los lectores. Los lectores te aguantan un montón de tonterías, y siempre están contentos de ver los libros que aman. No vas a desplazar el amor que le tiene un lector a un libro, y los lectores hacen mucho por los libros. Nos perdonan todos los defectos de nuestra escritura, llenan los huecos que dejamos en nuestros calendarios; si nuestras tramas no funcionan del todo bien, los lectores las remiendan para hacer que funcionen. Los lectores están contentos de verte. Cuando, como escritor, entendí que en realidad estaba escribiendo para lectores, empecé a ser bueno con los lectores. Mientras lograra los placeres clásicos del personaje y la narración, estarían en sintonía. Los lectores de El Señor de los Anillos aguantan miles de imágenes de poesía élfica, ¡y ni siquiera entienden toda esa mierda! El punto de partida para concebir una voz para los lectores es tratar de armonizar con la generosidad de la forma en que nos movemos. Ojalá más escritores dejaran de estar pendientes de otros escritores y se concentraran en los lectores, gente generosa que es más inteligentes de lo que la mayoría de los escritores creemos. Cuando oigo a mis alumnos decir “eso tiene un exceso de una lengua extranjera”, les pregunto: “¿en qué lectores estás pensando?”. Antes de que podamos arribar a una voz siempre les digo: “hay que entender la idiosincrasia de la lectura para que, al menos, sepan dónde están parados”. Cuando cuentas con un entorno generoso es mucho más probable que experimentes con tu voz, y es mucho más probable también que seas tolerante con tus errores.

AP: ¿Por qué Junot Diaz no ha escrito ciencia ficción ni fantasía? ¿Crees que, a pesar de que es parte de tu idiosincrasia de la lectura, las restricciones formales del género no te interesan en términos de formato, o podemos esperar que lances tu propia trilogía un día?

JD: Sí, me fascinan todos los géneros nerd. Si hubiera un concurso de nerds, tal vez no quedaría entre los mejores diez o en el equipo olímpico pero sí tendría una buena oportunidad. En parte tiene que ver con mis limitaciones como escritor. He tratado de escribir cosas así pero soy excepcionalmente malo para este tipo de géneros. Hasta mis amigos lectores más tolerantes dirían: “¡Tío, no le enseñes esto a nadie!” En parte es porque soy lento. Estoy tratando de escribir una novela apocalíptica de monstruos bastante rara. En todo momento tengo sueños. No conozco a nadie que haya crecido en una casa con esos cuadros católicos enormes y espeluznantes. Había uno en mi casa de San Miguel aplastando a un diablo de tez oscura con una de esas espadas curvas que usan los ángeles. Cuando era niño, era como si midieran más de diez metros, y siempre tuve la idea de que un día escribiría una historia sobre monstruos de diez metros que eran medio angelicales, pero a nadie le gustó.

AP: Bueno, volviendo a tu colección de cuentos, estaba pensando en ellos en relación con Oscar Wao. Él tiene tal corazón abierto que, hasta cierto punto, es su perdición. ¿Crees que Yunior padece lo mismo? Parece habitar un área de la pérdida más que del amor, como siempre en duelo. ¿Podrías hablarnos un poco de Yunior? ¿Te ves trabajando con él en el futuro?

JD: Creo que siempre pensé en este tipo de historias de una manera un poco simplista; creo que generan una oportunidad para que la gente se encuentre a sí misma. No tanto que uno salga del arte sanado o mejorado de cierto modo, pero tiene la capacidad de hablarle a aquellos que pasan su tiempo en esta sociedad pensando en nuestro yo humano, con defectos, imperfecto, pero radicalmente bello. El arte nos da la oportunidad de estar en esa presencia humana, y eso suele ser muy difícil. Yo me pasé la mayor parte del tiempo fingiendo ser mejor de lo que era, como si no debiera tener defectos o cometer errores. Se supone que no tenemos que estar en conflicto y debemos ser máquinas de funcionamiento perfecto, pero el arte nos da la oportunidad, por un momento, de quitarnos la máscara. En lo que respecta a Yunior, supongo que es un personaje que, como muchos de nosotros, tuvo una infancia notablemente difícil. No saca provecho de nada de eso, lo que siempre me fascinó. Como personaje, nunca cuenta que tiene un padre que lo desprecia, pierde su país natal, su migración no fue linda, su mamá es prácticamente indiferente, está mucho más interesada en su hermano, su hermano está cerca de ser un sociópata que no tiene ningún problema en sacarle un ojo a su hermano para ganar puntos… No es la mejor infancia. Realmente no saca nada de ahí y tampoco cuenta sus sufrimientos. Creo que el problema de Yunior con sus relaciones viene en este contexto. Es alguien que se protege, que se ha tenido que encerrar en sí mismo para sobrevivir, pero está desesperado por un amor. Con Yunior pienso mucho sobre la idea de que nuestro pasado nos acecha de algún modo, que presenta argumentos en contra nuestra que tenemos que contrarrestar con nuestra vida entera. Su pasado le pesa y, definitivamente, tiene que encontrar una manera de contarlo. Está atorado en esta historia rara que trata de entender, y creo que la mayoría de nosotros estamos así.

AP: Dijiste antes que con frecuencia la sociedad es indiferente a las artes. ¿Cómo llegaste a escribir, qué te sostuvo? Quizá podrías contarnos un poco del momento crucial…

JD: Creo que es una de esas historias que muchos de nosotros tenemos como “narrativas”; vengo de una familia migrante eminentemente práctica. Una familia militar. Mi padre estaba en el ejército dominicano, mi hermano menor es un marine veterano de combate que volvió de Irak hace poco, mi hermana se casó con un militar… La idea de que uno de nosotros se convertiría en artista era absurda porque éramos muy pobres, siempre estábamos ahorrando; acudíamos a los programas de asistencia social, todo eso. Fue una jugada colosalmente impráctica, pero es parte de lo que mueve estas cosas… Mi escritura viene de mi amor por la lectura. Escribir sería imposible para mí si no amara tanto leer. Soy un lector muy lento. Escribir me parece horriblemente difícil; nunca he sido un escritor fluido. Nunca he dicho: “ah, qué buen día tuve escribiendo”, pero muchos de mis amigos lo dicen. Lo que pasa con alguien como yo es que te enfrentas a una resistencia pétrea de parte de tu familia, una resistencia de adamianto cuando te das cuenta de lo difícil que es el trabajo. Lo que hace esto posible para mí es mi adoración por los libros. Cuando era niño, todo el tiempo soñaba con libros que nunca se escribieron, como el quinto libro de El Señor de los Anillos, y siempre lo encontraba en la biblioteca pero me despertaba antes de poder sacarlo; esto me pasaba cada noche. Parte de ello, claro, es este entusiasmo por leer, y creo que me sirvió de motor. Si amas algo lo suficiente, te ayuda a mitigar el desánimo. Y también, como migrante, era un niño súper práctico. Nunca fui uno de esos artistas que piden que los mantengan durante meses mientras escriben. Siempre trabajé, entregando mesas de billar, en una acería y mil trabajos horribles más, porque en mi mente siempre está la idea de “dar al César lo que es del César”. Así que trabajaba y luego, de noche, escribía; y pensé que así iba a ser mi vida, pensé que iba a tener un trabajo mosaico regular. Parte de la razón por la que creí que podía hacer esto fue la noción de que amo tanto estos libros que en los sueños me mantendrían a flote. Recuerdo el día que me desperté en mi dormitorio de la universidad y me di cuenta de que sería muy difícil para mí convertirme en abogado o estudiar.

AP: ¿Qué piensas sobre la obra prohibida en Tucson, Arizona?

JD: Más allá de mi declaración personal sobre lo que significa que alguien prohíba tu obra, hay un asunto más importante que estás trayendo a colación. Estamos en un momento histórico perverso en este país. No podemos separar la prohibición de los libros culturales con temas latinos en Arizona del ataque actual y total a los programas de estudios étnicos en todo el país. Tampoco podemos separar el hecho de que los programas de estudios étnicos consistentemente les brindan a los jóvenes un lente crítico a través del cual tratamos de ver y mejorar nuestra democracia. Si tomas una clase de estudios étnicos, vas a ser un miembro mucho mejor de nuestra sociedad que si no lo tomaras. Pero, como sabes, la razón por la que eres un mejor miembro es porque de pronto cuentas con un lente racial, cultural, de género y de clase con el cual enfocar el mundo, y eso perturba profundamente a estos imbéciles que quieren prohibir estas cosas. Encima de todo, no puedes desligar nada de eso de la ola perversa, inhumana de actividad antilatina que está atacando este país. ¡Es la locura! La manera en que hemos victimizado a la comunidad latina, la forma en que la satanizamos continuamente, es como un pase libre para todos. Si alguien me hubiera dicho que las verdaderas víctimas nacionales del 11 de septiembre fueron la comunidad latina, me habría sorprendido, pero lo habría creído. Supongo que en un lugar como Arizona todo se combina más explícitamente, pero como nación, lo que le damos a nuestro “grupo minoritario más grande”, a cuya labor indocumentada somos todos tan adictos, no es otra cosa que cobardía, menosprecio y crueldad. Creo que algún día tendremos el presidente que nos merecemos. No lo tenemos ahora, pero vamos a lograr un liderazgo que no crea que es buena idea afligir a la gente más vulnerable de nuestra comunidad, y creo que no hay un indicador más claro de la caída del carácter nacional que un país que aflige a los débiles.